The Nazi concentration camps during World War II were a place of unimaginable horror and suffering for millions of innocent people.

The Nazi concentration camps during World War II were a place of unimaginable horror and suffering for millions of innocent people.

While much attention has been paid to the role of male guards in committing these atrocities, the role of female guards in these camps has often been overlooked.

These women were tasked with enforcing the strict rules and regulations of the concentration camps, but also played a crucial role in the torture, abuse, and murder of countless prisoners.

The psychology of these female guards is a complex and disturbing subject. Some researchers believe they were driven by a desire for power and control, as well as a sense of loyalty to the Nazi cause.

Others suspect that they may have suffered from various psychological problems such as sadism or sociopathy, which made them more prone to acts of violence and cruelty.

Despite their blatant disregard for human life and the immense suffering they inflicted on others, many of these guards escaped punishment after the war.

Some went into hiding, others were able to blend in with the population. A few, however, were tried and convicted for war crimes. Some received life sentences or even the death penalty.

Marta Löbelt, telephone operator, Gertrud Rheinhold, Irene Haschke, and Anneliese Kohlmann shortly after their arrest in Bergen-Belsen, May 2, 1945. The first three are wearing their Nazi uniforms, while Kohlmann is wearing an ill-fitting men’s uniform, as she was wearing a prisoner’s uniform at the time of her arrest and attempted to disguise herself as a Jew. (May 2, 1945)

Of the 50,000 guards in the concentration camps, approximately 5,000 were women. In 1942, the first female guards arrived at Auschwitz and Majdanek from Ravensbrück.

The following year, the Nazis began recruiting women as overseers due to a shortage of male guards. In these camps, the German job title “Aufseherin” (female) means “supervisor” or “guardian.”

The female guards generally belonged to the lower to middle class and had no relevant professional experience; their professional backgrounds varied: one source mentions former head nurses, hairdressers, tram conductors, opera singers, or retired teachers.

Volunteers were recruited through advertisements in German newspapers urging women to demonstrate their love for the Reich and join the SS-Gefolge (a support and service organization of the Schutzstaffel (SS) for women). Some were also drafted based on information in their SS files.

For many women, admission to the League of German Girls as adolescents served as a form of indoctrination. At one of the postwar hearings, senior female guard Herta Haase-Breitmann-Schmidt, the leading female guard, claimed that her female guards were not fully-fledged SS women.

As a result, some courts disputed whether the female SS helpers deployed in the camps were official members of the SS, leading to contradictory court rulings. Many of them belonged to the Waffen-SS and the SS-Helferinnenkorps.

Prisoners in Sachsenhausen lined up for roll call, 1941.

In many camps, there were reportedly relationships between SS men and female guards, and Heinrich Himmler had ordered the SS men to treat the female guards as equals and comrades.

In the relatively small Helmbrechts subcamp near Hof, camp commandant Wilhelm Dörr openly maintained a sexual relationship with the senior warden Herta Haase-Breitmann-Schmidt.

Corruption was another aspect of the female guard culture. Ilse Koch, known as “The Witch of Buchenwald,” was married to the camp commandant, Karl Koch. Both were accused of embezzling millions of Reichsmarks. Karl Koch was convicted and executed by the Nazis for this, just weeks before Buchenwald was liberated by the US Army.

An obvious exception to the prototype of the brutal female guard was Klara Kunig, a camp guard who served in the Ravensbrück concentration camp and its Dresden-Universelle subcamp in 1944.

The camp director pointed out that she was too polite and friendly toward the inmates, which led to her dismissal from camp service in January 1945. Since February 13, 1945, the day of the Allied bombing of Dresden, her fate has been unknown.

Grese in August 1945 while awaiting trial.

Irmgard Ilse Ida Grese (October 7, 1923 – December 13, 1945) was a guard at the Ravensbrück and Auschwitz concentration camps and served as head of the women’s department at Bergen-Belsen. She was a volunteer member of the SS.

As a teenager, Grese wanted to join the League of German Girls, the girls’ branch of the Hitler Youth, but her father forbade it. Before her 17th birthday, she moved to the SS Auxiliary Women’s Training Base near the Ravensbrück women’s concentration camp.

In 1940 she became a guard in Ravensbrück and in March 1943 she was transferred to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Due to her transfer, Grese came into conflict with her father that same year, as he had vehemently opposed her joining the SS leadership. He expelled her from his house. Grese participated in the selection of prisoners for the gas chambers at Auschwitz.

Irma Grese and former SS-Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer in Celle prison in August 1945.

In early 1945, Grese accompanied a prisoner transport from Auschwitz to Ravensbrück. In March, she and a large number of prisoners from Ravensbrück went to Bergen-Belsen. Grese was captured by the British Army on April 17, 1945, along with other SS members who did not escape.

Grese was one of the 45 people accused of war crimes in the Belsen Trial in Lüneburg, Lower Saxony.

During the trial, the press referred to Grese as “the beautiful beast” alongside former SS-Hauptsturmführer Josef Kramer (“the Beast of Belsen”), the former commandant of Birkenau.

Grese and Josef Kramer (known as the Beast of Belsen) after their capture – Kramer was also executed for his crimes.

After a nine-week trial, Grese was sentenced to death by hanging. Although the charges against some of the other guards (16 in total) were just as serious as those against Grese, she was one of only three guards sentenced to death.

Grese and two other concentration camp employees, Johanna Bormann and Elisabeth Volkenrath, were sentenced to death along with eight other men for crimes committed at Auschwitz and Belsen. When the verdicts were read, Grese was the only prisoner who remained defiant. Her subsequent appeal was rejected.

Grese at the Belsen Trial in 1945.

According to Wendy Adele-Marie Sarti, Grese sang Nazi songs with Johanna Bormann until the early hours of the morning the night before her execution.

On December 13, 1945, Grese was led to the gallows in Hameln Prison. The women were executed individually by hanging, and the men were subsequently executed in pairs.

Ilse Koch around 1947.

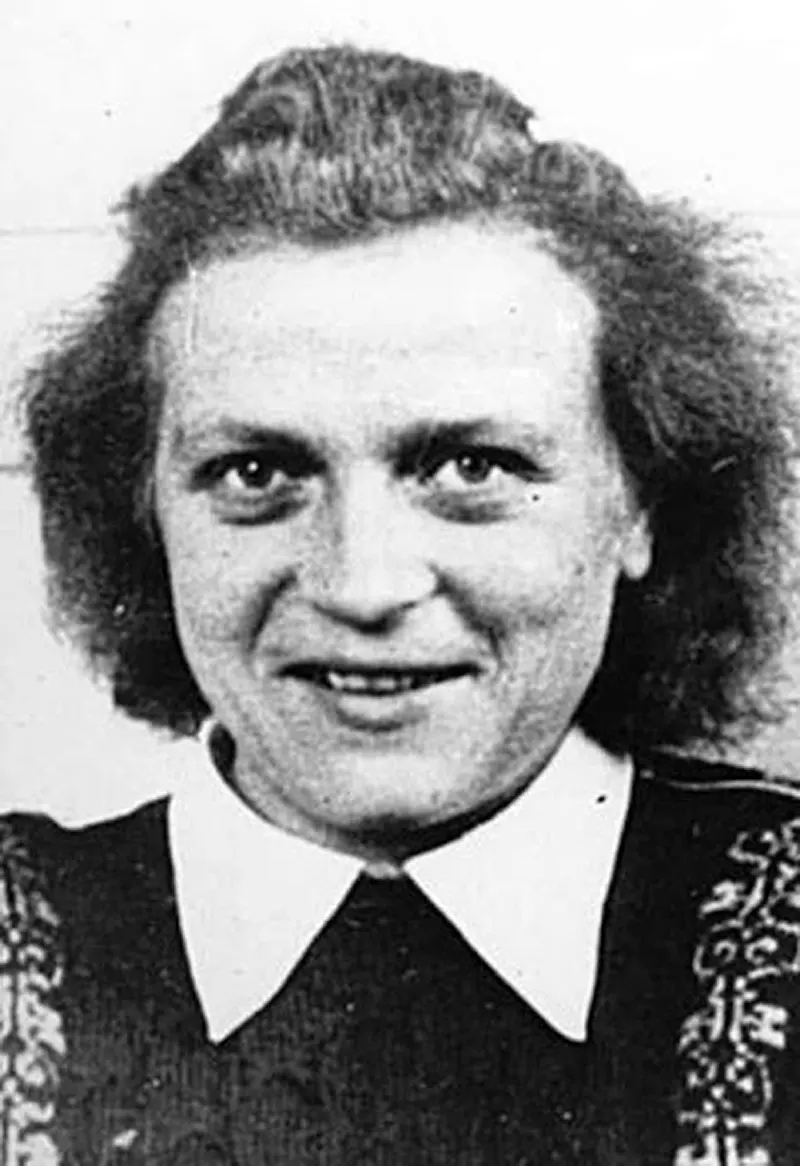

Ilse Koch , also known as the “Witch of Buchenwald,” was one of the most notorious war criminals of the Nazi regime.

Koch was born in Dresden in 1906 and later married Karl Koch, the commandant of the Buchenwald concentration camp.

As the wife of a high-ranking SS officer, Koch wielded considerable power and was known for her sadistic treatment of prisoners.

Koch was particularly obsessed with collecting human skin, which she used to make lampshades, book covers, and other household items.

She is also known to have tattooed prisoners’ skin to expand her collection. However, Koch’s sadistic behavior was not limited to her collection of human skin.

She was also known to have participated in the torture and murder of prisoners, including children. Her actions were so heinous that even other SS officers found her behavior repulsive and questioned her sanity.

Ilse Koch, known to her protégés as the “Witch of Buchenwald.”

After the war, Koch was arrested by American authorities and tried for war crimes. She was eventually sentenced to life imprisonment. However, the case was controversial because there was no concrete evidence of specific crimes.

There were also rumors that Koch was protected by higher-ranking SS officers who were afraid of what she might reveal about her own crimes.

Ilse Koch before the US military tribunal in Dachau, 1947.

Ilse and Karl Koch had a son and two daughters. Their son committed suicide after the war “because he couldn’t live with the shame of his parents’ crimes.”

Another son, Uwe, was conceived in her prison cell in Dachau with a German cellmate. He was born in Aichach Prison near Dachau, where Koch was serving her life sentence, and immediately taken away from her. At the age of 19, Uwe Köhler learned that Koch was his mother and began visiting her regularly in Aichach.

Koch hanged herself on September 1, 1967, at the age of 60 in the Aichach women’s prison. She suffered from delusions and was convinced that concentration camp survivors were abusing her in her cell.

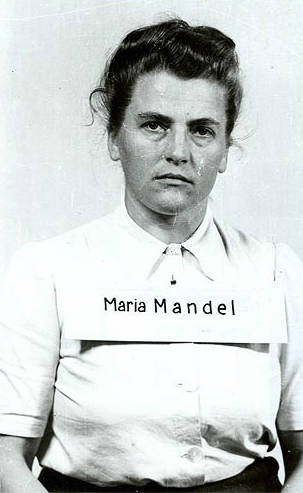

Maria Mandl after her arrest by US troops in 1945. She was a high-ranking official at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and responsible for the deaths of over 500,000 female prisoners.

Maria Mandl (also spelled Mandel; January 10, 1912 – January 24, 1948) was an Austrian SS collaborator, known for her role in the Holocaust as a high-ranking official at the Auschwitz-Birkenau extermination camp. There, she is believed to have been directly involved in the deaths of over 500,000 prisoners. She was executed for war crimes.

According to some reports, Mandl often stood at the gate to Birkenau, waiting for a prisoner to turn around and look at her. Anyone who did so was taken out of line and never heard from again.

At Auschwitz, Mandl was known as “the Beast” and participated in death selections and other documented abuses over the next two years.

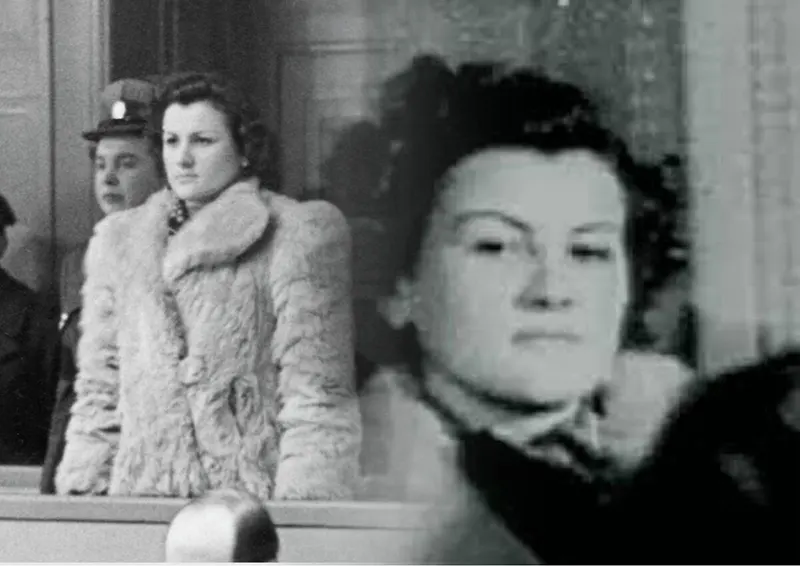

Mandl after her extradition to Poland, 1946.

The following is a firsthand account of Mandl’s treatment of prisoners upon their arrival at Auschwitz, presented by Jewish prisoner Sala Feder to the District Court in Kraków on December 1, 1947.

In August 1943, I was deported to Auschwitz along with my family (27 people, including nine children aged between one month and eleven years) in a transport of about 5,000 people from the ghetto in Środula near Sosnowiec.

At the ramp in Birkenau, the transport was awaited by the defendant Mandl, accompanied by SS woman Margot Dreschel, and as soon as the transport arrived, Mandl carried out a selection and sent about 90 percent of the transport into the wagons that took these people to the nearby crematorium.

[…] During these selections, the defendant Mandl tortured the prisoners in a cruel manner by beating the women, men and children with a whip and kicking them blindly.

She tore the children from their mothers’ arms, and when the mothers tried to approach and defend the children, Mandl beat and kicked the mothers terribly.

I saw – right next to me – a young, 20-year-old mother trying to reach her two-year-old child, who was thrown onto the car and was being kicked and beaten so cruelly by Mandl that she could no longer get up.

[…] I was holding my four-year-old child by the hand. The defendant Mandl approached me, snatched my child away, and threw it onto a still-empty wagon, injuring the child’s face and causing him to cry and call for me. However, I was deported to the group that was not loaded onto the wagons.

As I tried to reach the crying child in the car, Mandl started hitting me so hard that I fell. Mandl continued kicking me even though I was on the ground and nearly knocked out all my teeth with her shoe.

Herta Bothe was waiting for her trial in Celle (August 1945).

Herta Bothe (January 3, 1921 – March 16, 2000) was a German concentration camp guard during World War II. After the defeat of Nazi Germany, she was imprisoned for war crimes and released early from prison on December 22, 1951.

She was said to be the tallest woman arrested; she was 1.91 m tall. Bothe also stood out because, unlike most SS women, she wore black boots while wearing regular civilian shoes.

The Allied soldiers forced her to bury the bodies of dead prisoners in mass graves next to the main camp. In an interview some sixty years later, she recalled that they weren’t allowed to wear gloves while carrying the bodies and that she was terrified of contracting typhus.

She said the bodies were so decomposed that their arms and legs were torn off when they were moved. She also recalled that the emaciated bodies were still so heavy that she suffered severe back pain. Bothe was arrested and taken to prison in Celle.

Female SS guards from the Bergen-Belsen camp are brought forward to recover the bodies. The women include Hildegard Kanbach (first from left), Magdalene Kessel (second from left), Irene Haschke (center, third from right), senior guard Herta Ehlert (second from right, partially obscured), and Herta Bothe (first from right).

At the Belsen trial, she was called an “unscrupulous guard” and sentenced to ten years in prison for using a pistol against prisoners.

Bothe admitted to hitting prisoners with her hands for violations of camp rules such as theft, but stressed that she never hit anyone “with a stick or a rod” and never “killed anyone.”

Her claim of innocence was considered questionable, as a survivor of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp claimed to have seen Bothe beat a Hungarian Jew named Éva to death with a wooden block. Another youth claimed to have seen her shoot two prisoners for reasons he could not understand. Nevertheless, she was released from prison early.

Camp guard Herta Ehlert from Bergen-Belsen was sentenced to 15 years in prison. This portrait was taken in Celle in August 1945.

Herta Ehlert (1914–1997) was a German SS guard and supervisor in several Nazi concentration camps during World War II, including Ravensbrück and Auschwitz-Birkenau.

She was known for her brutality and her involvement in the selection and execution of prisoners. After the war, Ehlert was arrested and tried for war crimes. In 1949, she was ultimately sentenced to life imprisonment. She was paroled in 1954 and led a relatively quiet life until her death in 1997.

Greta Bösel during the trial.

Greta Bösel was a guard at the Ravensbrück women’s camp. A trained nurse, she served as a labor leader and, among other things, selected women for the gas chamber.

Greta is known for her aphorism: “If they can’t work, let them rot.” She was convicted in the first Ravensbrück trial. The court found her guilty. The Allies hanged her along with others in Hamelin Prison on May 3, 1947.

Elisabeth Volkenrath, senior guard at Ravensbrück, Auschwitz, and Bergen-Belsen. She was hanged in November 1945.

Notice how many of the top guards at Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in this list are women.

A group portrait of female guards at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

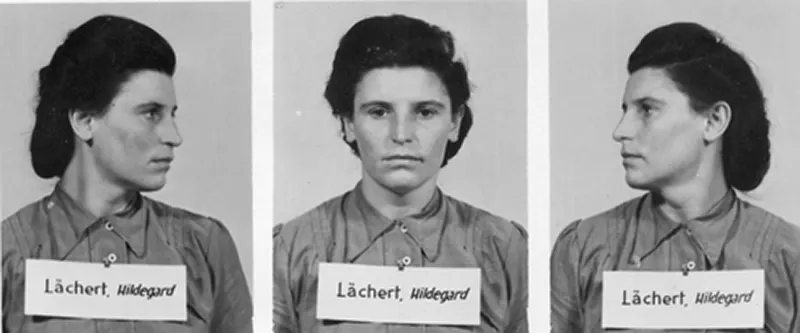

Hildegard Lächert.

Hildegard Lächert was nicknamed “Bloody Brigitte” (in Polish, “Krwawa Brygida”). Many witnesses described her as the “worst” or “cruelest” guard, a “beast,” and the “terror of the prisoners.”

For her involvement in the selection for the gas chamber, the abandonment of her dog to prisoners, and her general mistreatment, the court sentenced her to twelve years in prison. Hildegard Lächert died in Berlin in 1995 at the age of 75.

Carmen Mory, a Kapo at Ravensbrück. She was sentenced to death by hanging, but committed suicide the night before her execution by slitting her wrists.

Jenny-Wanda Barkmann at the Stutthof trials in 1946.

Jenny-Wanda Barkmann (May 30, 1922 – July 4, 1946) was a German guard in Nazi concentration camps during World War II.

In 1944, she became a guard at the Stutthof SK-III women’s subcamp, where she mistreated prisoners and killed some of them.

She also selected women and children for the gas chambers. She was so merciless that the female prisoners nicknamed her “Beautiful Ghost.”

Jenny Barkmann was quite stylish during the trial.

Barkmann fled Stutthof as the Soviet Red Army approached. She was arrested in May 1945 while attempting to leave a train station in Danzig. She became a defendant in the first Stutthof trial, in which she and other defendants were convicted for their crimes at the camp.

Barkmann reportedly giggled and flirted with her prison guards during the trial. She was apparently observed adjusting her hair while testifying. She was found guilty, after which she declared, “Life is indeed a pleasure, and pleasures are usually short.”

Barkmann was publicly executed by hanging on July 4, 1946, along with ten other defendants in the trial, on Biskupia Górka Hill near Gdansk. She was 24 years old and the first to be hanged.

Guards of the Stutthof concentration camp at a trial in Danzig from April 25 to May 31, 1946. First row (from left): Elisabeth Becker, Gerda Steinhoff, and Wanda Klaff. Second row: Johann Pauls, Erna Beilhardt, and Jenny-Wanda Barkmann.

The Stutthof Trials were a series of war crimes tribunals held in post-war Poland aimed at prosecuting staff and officials of the Stutthof concentration camp, who were responsible for the murder of up to 85,000 prisoners during the Nazi occupation of Poland in World War II.

Stutthof was liberated by the Soviets on May 10, 1945. Commandant Johann Pauls and his staff were tried before the Polish Special Court in Danzig between April 25 and May 31, 1946.

Five women and six men were found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to death. Johann Pauls, the SS guards Jenny, Wanda Barkmann, Elisabeth Becker, Wanda Klaff, Ewa Paradies, Gerda Steinhoff, and five other men pleaded not guilty, and the women seemed to disregard the trial until the end.

The defendants with Polish guards on the grounds of the Stutthof concentration camp. First row from left to right: Ewa Paradies, Elisabeth Becker, and Wanda Klaff. Second row: Gerda Steinhoff and Jenny Barkmann.

Johanner Altvater.

Johanna Altvater was born in Germany in 1920. In 1942, she came to the Vladimir-Volynsky region of Ukraine to work as secretary to the Nazi Party district leader Wilhelm Westerheide.

After the war, she was accused of holding a Jewish boy by the legs and killing the child by smashing his head against a wall in a ghetto.

She was also accused of throwing Jewish children out of a third-floor window of a hospital and then sending staff to the sidewalk to ensure that all the children were dead.

After the war, she married and took her husband’s surname, Zelle. She worked as a social worker for some time, but was eventually brought to trial along with her former superior, Westerheide.

They were finally acquitted by a lower court in 1979 and again by a higher court in December 1982, both times due to conflicting witness statements and a general lack of evidence.

Female guards in the Ravensbrück concentration camp (photo taken around 1940).

Despite the cruel crimes they committed, few of the female guards were convicted after the war.

SS women arrive at an SS holiday camp in the town of Porąbka in then-German-occupied Poland. ( More photos and background information here .)

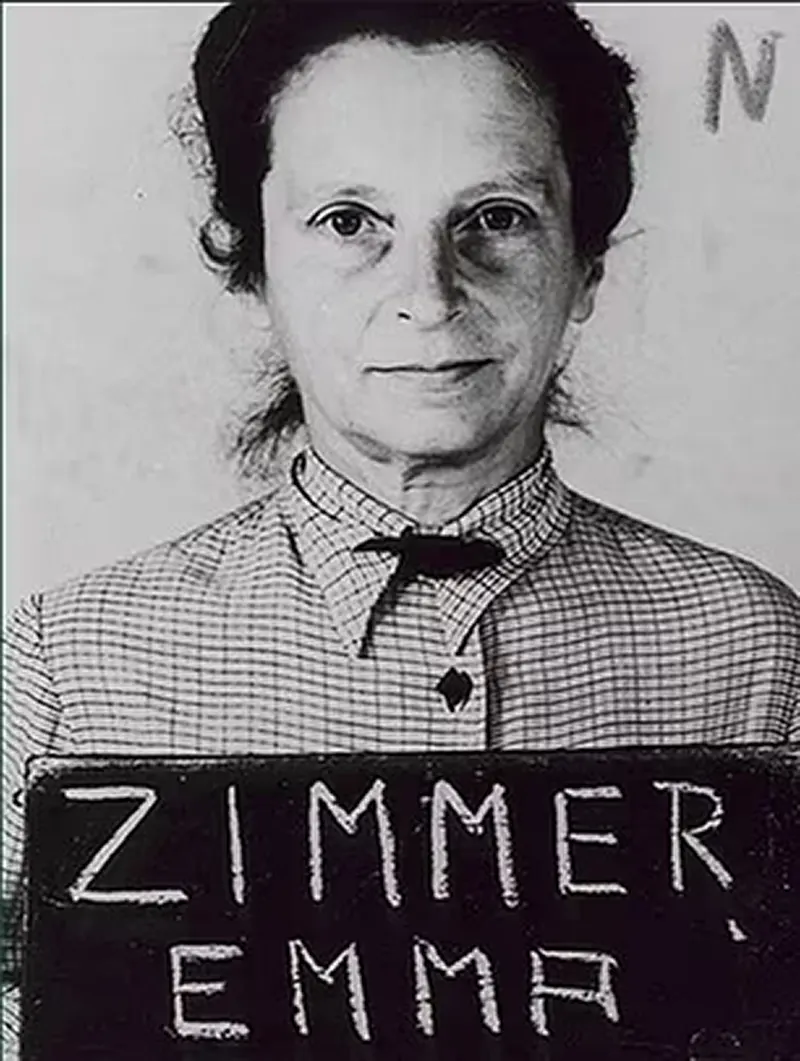

Emma Zimmer, who worked as an SS guard in three concentration camps, was later sentenced to death by hanging by a British military court.

Another SS guard sentenced to death was Therese Brandl (right), who worked in three concentration camps between 1940 and 1945.

Luise Helene Elisabeth Danz worked at the Auschwitz concentration camp from September 1944, where she was the reporting manager in section BIIb in Birkenau.

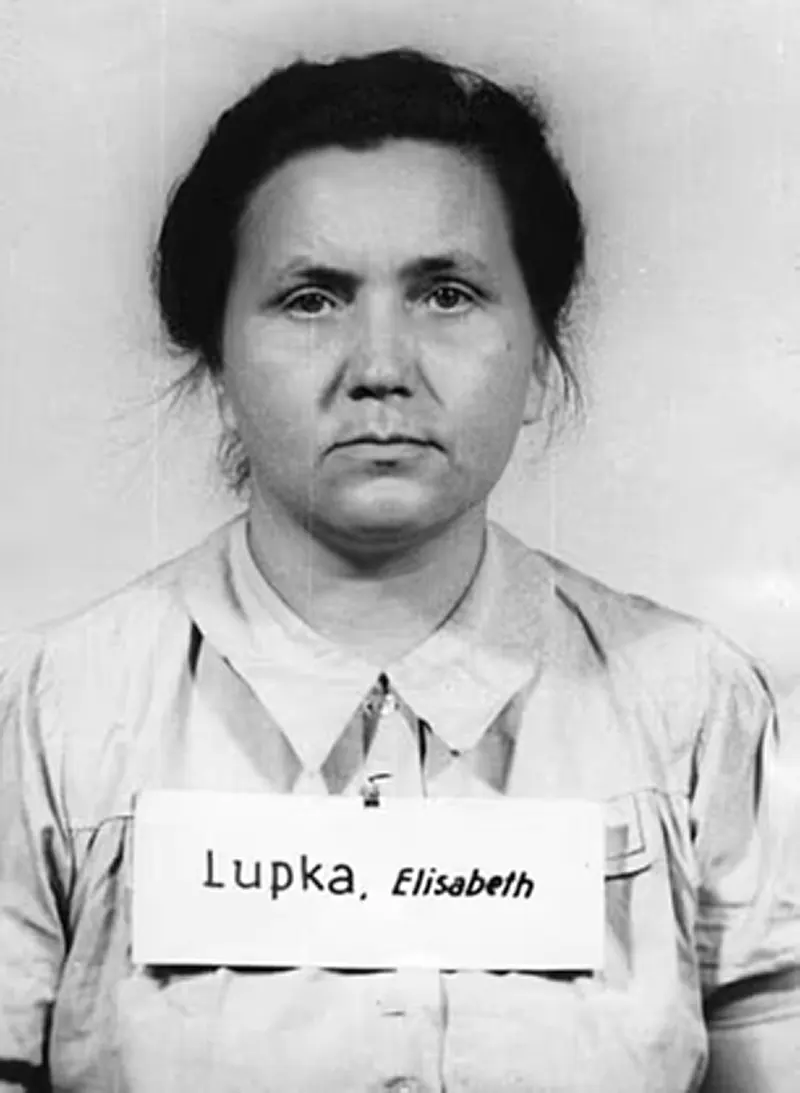

Elisabeth Lupka was sentenced to death after working at Auschwitz for two years between 1943 and 1945.

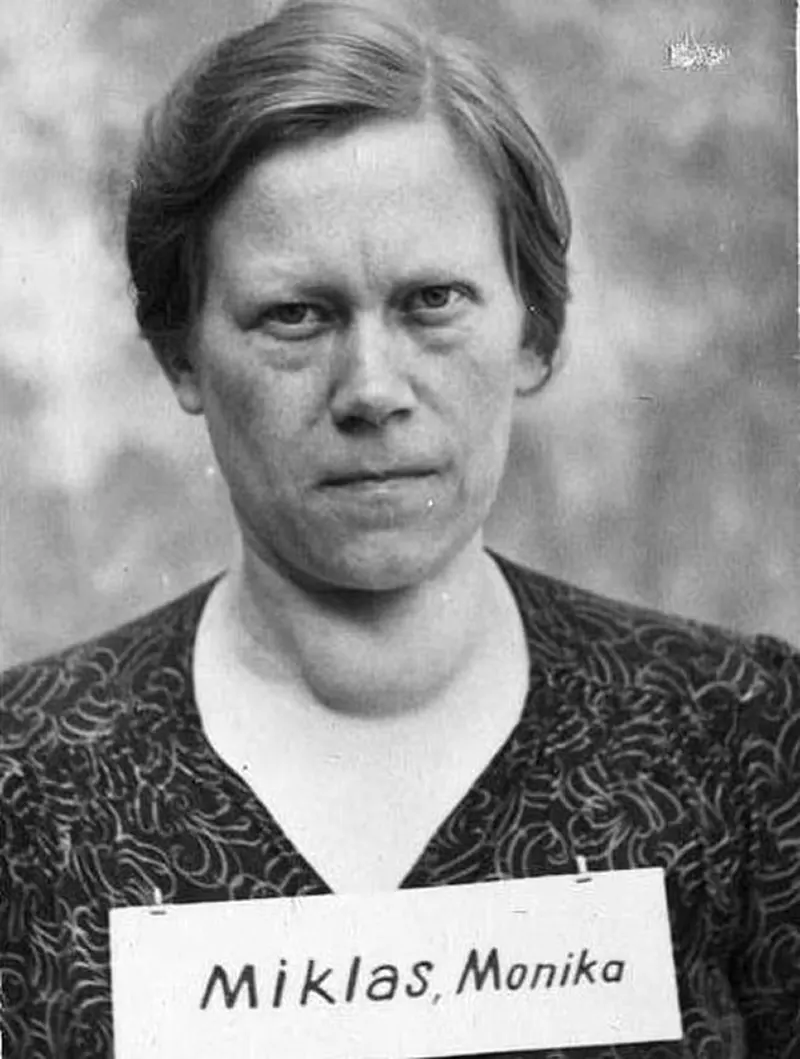

Monika Miklas, who worked as an SS guard in the Auschwitz concentration camp from April 1943.